Metabolic Downregulation in Rapid vs Moderate Deficits

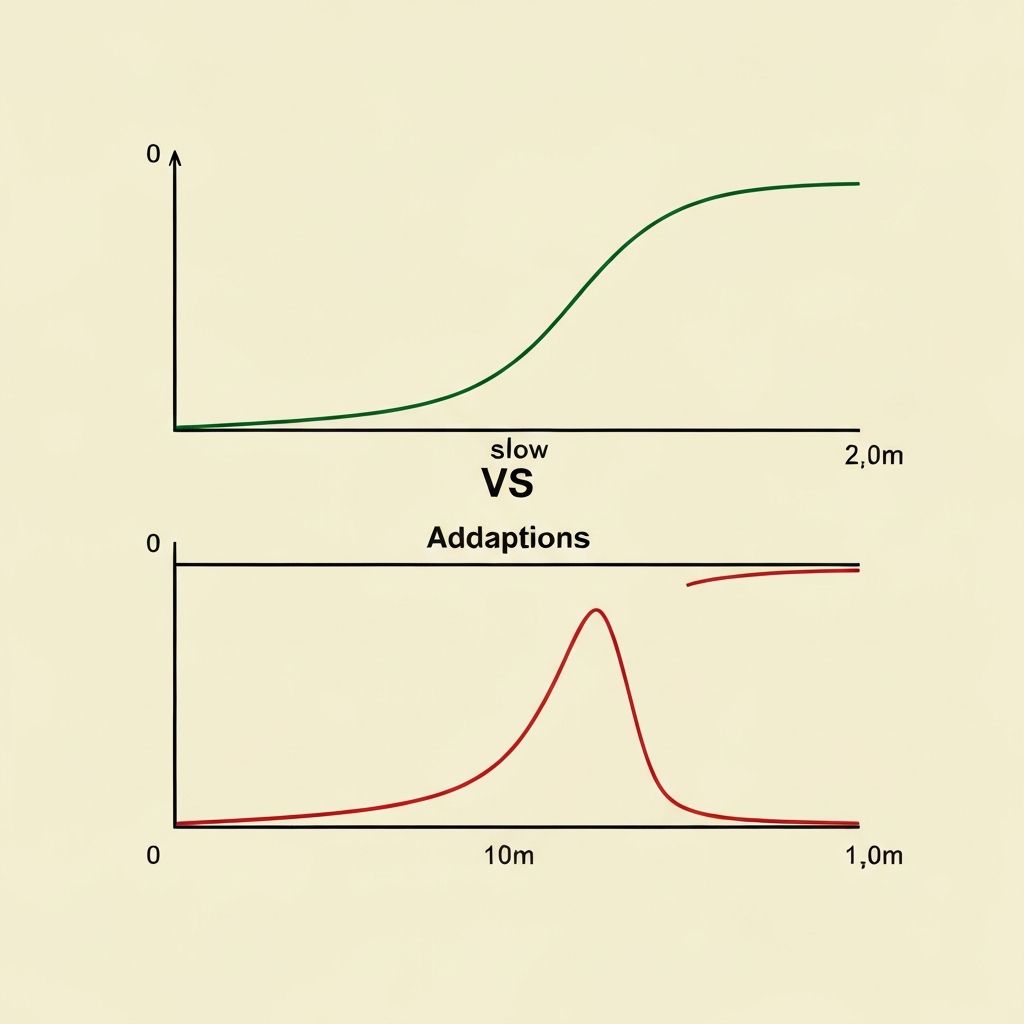

Examination of adaptive thermogenesis differences between rapid and gradual energy restriction approaches.

Introduction

Metabolic adaptation represents one of the most significant physiological responses to caloric restriction. This phenomenon involves the body's reduction in energy expenditure as it responds to reduced energy availability. The magnitude and speed of this adaptation varies substantially depending on the rate of energy deficit.

Defining Metabolic Adaptation

Metabolic adaptation (also termed adaptive thermogenesis) encompasses several mechanisms:

- Reduced basal metabolic rate (BMR)

- Decreased thermic effect of food (TEF)

- Reduced non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)

- Suppressed hormonal signaling affecting energy expenditure

Rapid Deficit Characteristics

Aggressive caloric restriction (creating deficits of 40-50% below maintenance) triggers rapid and substantial metabolic adaptation:

- Magnitude: 20-30% reduction in total daily energy expenditure after 4-8 weeks

- Speed: Metabolic rate begins declining within 7-10 days of aggressive restriction

- Hormonal Changes: Sharper declines in T3 (thyroid hormone), leptin, and norepinephrine

- Sustainability: Greater metabolic suppression persists weeks after restriction ends

Moderate Deficit Characteristics

Gradual caloric restriction (creating deficits of 20-30% below maintenance) produces slower, smaller-magnitude adaptation:

- Magnitude: 10-15% reduction in total daily energy expenditure after 8-12 weeks

- Speed: Gradual metabolic decline develops over 3-4 weeks

- Hormonal Changes: More gradual reductions in thyroid hormones and compensatory signals

- Sustainability: Slightly smaller post-restriction metabolic suppression effect

Research Findings

Meta-Analysis Data: Systematic reviews comparing restriction rates show 15-25% greater metabolic slowing in rapid deficit groups when measured at equivalent total mass loss timepoints. A controlled study comparing 500 kcal/day moderate deficit versus 1000 kcal/day rapid deficit found metabolic adaptation was roughly 1.5-2.0 times greater in the rapid group.

Hormonal Markers: Prospective studies measuring hormone concentrations show T3 (triiodothyronine) decline 2-3 times steeper in rapid restriction. Leptin suppression occurs more sharply. Norepinephrine (which supports metabolic rate) declines more substantially in aggressive approaches.

Thermic Effect of Food: Research indicates the thermic effect of food—energy required for digestion—declines more substantially in rapid restriction, contributing to overall metabolic adaptation effect.

Compensation Mechanisms

The body activates stronger compensatory responses during rapid restriction:

- Sympathetic Nervous System: Despite overall metabolic suppression, acute stress hormone activation (cortisol) may be more pronounced with rapid restriction

- Hormonal Signaling: More aggressive suppression of metabolic hormones triggers stronger adaptation

- Behavioral Compensation: Increased hunger signaling and reduced activity (consciously or unconsciously) during rapid loss

Practical Implications

Greater metabolic adaptation in rapid approaches has several practical consequences:

- Plateau effects occur sooner in rapid loss (typically 3-6 weeks)

- Caloric intake must be progressively reduced to maintain loss rate

- Post-restriction metabolism remains suppressed 2-3 times longer in rapid approaches

- Recovery of metabolic rate occurs more slowly after rapid restriction ceases

Individual Variation

It's important to recognize substantial individual differences in adaptation magnitude. Factors influencing adaptation response include:

- Starting body composition and metabolic health

- Age and sex (older individuals and women may show greater adaptation)

- Duration of restriction

- Genetic factors affecting metabolic responsiveness

- Concurrent exercise and muscle preservation efforts

Duration Effects

The speed of metabolic adaptation also depends on restriction duration. Adaptation doesn't plateau instantly—it continues to deepen over months of consistent restriction. Research suggests adaptation reaches maximal levels after 8-12 weeks in moderate approaches and 4-6 weeks in rapid approaches.

Context and Meaning

Metabolic adaptation represents a normal physiological response—not a malfunction. The body's ability to reduce energy expenditure when energy is scarce reflects biological efficiency. However, the magnitude of adaptation affects practical weight loss progression and post-restriction metabolic environment.

Conclusion

Rapid energy deficits trigger 15-25% greater metabolic adaptation compared to moderate approaches. This adaptation develops faster, reaches greater magnitudes, and persists longer after restriction ends. Understanding these physiological responses provides context for interpreting loss rate changes and post-restriction metabolic patterns. Both rapid and moderate approaches activate adaptation; the differences are in magnitude and timeline rather than presence or absence.